|

History

The original church on this site was said to have been one of those founded

by San Magno (Saint Magnus) in the 7th century. One

was certainly built here by Doge Agnello Partecipazio in 828. It was

dedicated to Zacharias, the father of John

the Baptist,

whose relics were sent as a gift to Venice by the Byzantine

Emperor Leo V while the church was being built - these are

under the second altar on the right. The convent of Benedictine nuns next

door is said to have been built at the same time and was for a while the

only convent in Venice, and many of its abbesses were the daughters of

doges.

The church and convent were historically closely connected with the doge –

he processed to the church every Easter Monday. On 13th September 864, after

attending vespers at the church, Doge Pietro Tradinico was set upon by

conspirators at the entrance gateway to Campo San Zaccaria and left to

die. The ensuing riot meant that fearful nuns had to wait until nightfall

to retrieve his body for burial. It was on this visit that Doge Tradinico

had been given the corno ducale the cap which all doges since have

worn. (In fact a total of three doges have been assassinated in the

streets around San Zaccaria.) Many doges were buried her from the mid-9th

to the late-12th centuries. The original 9th-century basilica was

built over in the 10th-12th centuries. It’s said that the original church

burnt down in the fire of 1105, with a hundred nuns suffocated.

Later the nuns sacrificed their orchard (for cash) to facilitate the

creation of Piazza San Marco by Doge Sebastiano Ziani. This work also saw

the demolition of the original church of

San Geminiano, which was in the

middle of the planned piazza, with the nun's orchard laying between it and

the lagoon and so taking up most of the space that the Piazza was to

cover. It’s not surprising then, given this connection, that the state

paid for the building of the San Zaccaria we see today. It was also favoured

with having the campo in front declared private property with gates

closing its two entrances. The convent was famous for the wealth and

licentiousness of its pampered and high-born nuns, which might also

explain those gates. The current church and convent were built by Gambello from

1444-65. Gambello died in 1481 and work was completed by Codussi from

1483-1504. The church was consecrated in 1543

The church

The 15th century church you see as you enter the campo is therefore

the third on the

site. The façade of the old gothic church is visible to the right of

the current church's façade, along with the attached Benedictine convent

complex,

which was closed down by Napoleon and is now a Carabinieri barracks. The

16th century colonnade to the left of the church (possibly by Codussi and

now walled up) was built over the original convent cemetery. The

truly special monumental façade of the main church shows the transition from late gothic

to renaissance, as Gambello’s lower two levels are surmounted by Codussi’s

more renaissance upper three colonnades topped by a characteristic semicircular

gable and supporting side quadrants with blind occuli, very obviously the

work of the same architect as the earlier, and simpler, façade of

San Michele In Isola.

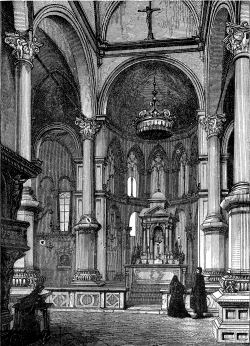

The interior

This is Gambello’s work, with the highlight the ambulatory that curves

around behind the altar with chapels radiating - a feature that is common

in France but rare in Italy and unique in Venice. It may have been

inspired by the one at the Benedictine mother-church at Cluny. Red ropes usually

prevent access though. The nave is short, with very wide aisles.

The piers have impressive capitals, carved by Giovanni Buora, and striking

bases. The grills through which the

nuns from the convent next door took part in services have long been

covered by big (and very ordinary) paintings. The

enormous lunettes lining the nave date to around 1684, are by the likes of

Zanchi, Fumiani and Celesti, and do not, for me, represent a high point in

Venetian art.

Art highlight

Giovanni Bellini’s Virgin and Child with Four Saints

over the second altar on the left (see right) is arguably the

pinnacle of his achievement in altarpieces, and certainly the best one

still in the place for which it was painted. It was painted

in 1505 when Bellini was about 74. This was the same year that Albrecht Dürer on a visit to Venice described him as 'very old and still the best

in painting'. It is painted as a continuation of the surrounding

architecture and seems to be a glowing window into another world. Put a

coin in the slot to light the light and let yourself be transported. The painting was

looted by Napoleon and kept in Paris for twenty years, before being

returned in 1817. During that time it was transferred from panel to

canvas. This scary process involves sawing away most of the wood panel

from the back of the painting and then dissolving the remaining wood down

to the back of the paint layer before gluing the paint layer to a new

canvas. Only in Paris could this have been done at the time and it is said

that this explains the painting’s fine state of preservation. But another

book says that the painting used to live over the first altar and was then in a

sorry state, due to damage and bad restoration, before it was restored in

1971. To fit into its current altar the painting, it is argued, had a strip cut from

bottom, so losing three rows of tiles and no little painted depth. A strip

at the top is also missing. Some

sources claim that these losses occurred during the painting's time in

Paris.

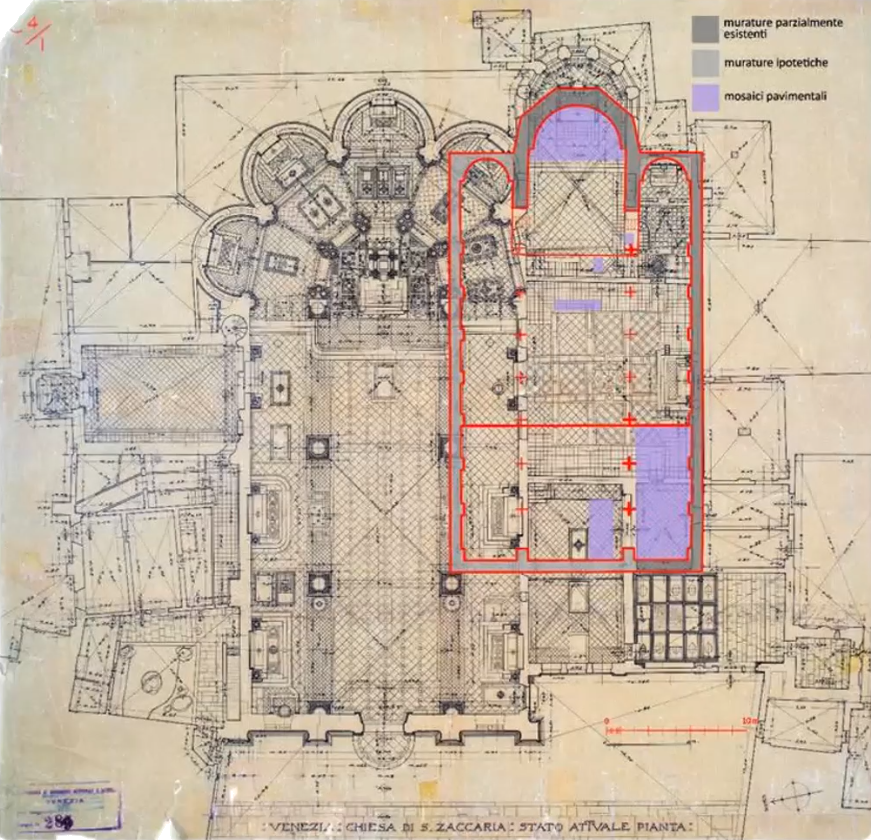

Through a door on the right are the

Three

chapels and the crypt

which formed parts of the old nun's church, outlined in red in the map

above.

The first is

the Chapel of Sant'Atanasio, which was most of the nave and right-hand

aisle of the old church, rebuilt for the nuns in the mid-15th century and

then converted into the chapel we see around 1595, when the inlaid choir

stalls for the nuns (signed and dated by Francesco and Marco Cozzi 1455-1464) were

installed. The chapel now contains an early Tintoretto altarpiece of the late

1550s, depicting

The Birth of John the Baptist or possibly The Birth of the Virgin.

An elderly man at the right edge might be Saint Zacharias himself, who you

would expect to be at his son's birth. The woman in the centre foreground

with the child on her knee is more convincingly claimed to be the Virgin,

due to the colouring of her

dress and her head being covered. There is

also

much scholarly debate over its original and subsequent position. It is

now over the altar, designed by Vittoria, and installed at the same time

as the altarpiece and the stalls. To the right of the

altar is The Flight into Egypt by Domenico Tintoretto, and there's

a lunette of the Resurrection of Christ with Adam and Eve by him in

here too. The

Crucifixion over the entrance door is claimed to be by Anthony van

Dyke and very redolent of the counter-reformation in its minimalness and

drama. much scholarly debate over its original and subsequent position. It is

now over the altar, designed by Vittoria, and installed at the same time

as the altarpiece and the stalls. To the right of the

altar is The Flight into Egypt by Domenico Tintoretto, and there's

a lunette of the Resurrection of Christ with Adam and Eve by him in

here too. The

Crucifixion over the entrance door is claimed to be by Anthony van

Dyke and very redolent of the counter-reformation in its minimalness and

drama.

A door takes you through to the Cappella dell'Addolorata (see

left), where

recent restoration work has discovered impressive marmorino

plasterwork decoration in the vaults from the 1460s, so not 19th-century

work as previously thought.

You then enter

the lovely Chapel of San Tarasio (see photo right).

This chapel was the presbytery and apse of the old nun's church, built in 1440/45 by Gambello.

It was partly built to house the relics of the order, including the bodies

of Saints Zaccaria and Tarasio and became a private

chapel for the nuns after the expansion later in the same century.

Fragments of tile floors from both the 9th-century (under glass at the back of the chapel) and the 12th-century (in front of the altar) are visible.

There are some very impressive frescoes in the vaulting by

the Florentine Andrea

del Castagno. An inscription says

that they were painted in 1442 - in collaboration with a certain

Francesco da Faenza - almost half a century

before the Renaissance finally took root in Venice. They are the

artist's earliest extant work and feature his only signature

(Andreas de Florentia). They were discovered in 1923 and cleaned in

the 1950s. The oddly youthful Saint Luke may be an early

self-portrait of the artist.

In this chapel you'll also find three well-preserved late-gothic

gilded altarpieces by brothers-in-law Antonio Vivarini and Giovanni

d’Alemagna. But the central three panels on the main level of the high altarpiece

(Saints Blaise and Martin, with The Virgin and Child Enthroned in the

centre) are signed and dated 1385 by Stefano di Sant'Agnese and were taken from

another work and

inserted in place of a reliquary in 1839. The two saints flanking

them (Mark and Elizabeth) are by Vivarini however.

There are more

saints (said to have also been added later) in panels on the back, in two

rows (see photo right) behind which panels were kept the depicted

saints' relics. There

is also a recently discovered and restored predella on the front of the

altar, which has been ascribed to Paolo Veneziano.

The very late-gothic style Saint Sabina Triptych is on the left-hand wall and the Polyptych of the

Body of Christ is on the right. Both are signed by Antonio Vivarini and Giovanni d’Alemagna and dated

1443 and are very old-style at a time when the Renaissance was raging in

central Italy. The frescoes and

altarpieces were

all paid for by individual nuns in the 1440s, from the wealthy Foscari

(Elena, the abbess and sister of the reigning Doge Francesco), Donà (Marina and Margharita) and Giustiniani (Agnesina)

families.

The 15th-century wooden statues on brackets on the side walls are Saints Zacharias

and Benedict. They were not originally positioned here but, it has been

suggested, were on the screen in the nun's church as part of a Crucifixion

scene with the polychrome wooden Crucifix until quite recently to be seen in the lower

dome of the main church, but very recently restored and now positioned by

the high altar at ground level.

The colonnaded 10th-century Romanesque crypt (see photo right)

under the Chapel of San Tarasio is another relic of the older church and

the eight tombs of early doges found down there are usually romantically

covered by lagoon water. Ongoing restoration work at the church has the

draining of the crypt planned, and the removal of the concrete floor to

reveal what is below.

Campanile 24m (78ft) manual bells

The first tower was demolished in the 11th Century and rebuilt in the

12th with recycled material. It's pyramid-shaped spire is visible in De

Barbari's map (see right). The spire and belfry collapsed in 1510

and the tower was rebuilt in its current spireless form.

Lost art

An early (c.1562) Paolo Veronese Virgin and Child Enthroned, with Saints

Joseph, Giustina, the young John the Baptist, Francis and Jerome (the Pala Bonaldi)

was looted by Napoleon from the sacristy here in 1797 and returned to the

Accademia in 1815. It looks influenced by Bellini, with a setting reminiscent of

his San Zaccaria altarpiece, but already has Veronese's characteristic

bustle and asymmetry. It was commissioned by Francesco Bonaldo, a procurator of San

Marco, as the altarpiece for the funerary chapel created for his brother

Girolamo and son Giovanni as part of his rebuilding in the sacristy here

in 1562.

All three name saints appear in the altarpiece.

The church in art

Francesco Guardi painted The Visiting Room of the Nuns at San Zaccaria.

The doge's visit to San Zaccaria on Easter Monday by

Gabriel Bella (see right) is in the

Querini Stampalia.

There's also a Canaletto (see right)

in a private collection. John Piper produced a lithograph of the façade in the early 1960s.

The church in literature

Mary Laven's

Virgins of Venice has a lot about the high-born reluctant nuns

here, and their consequent unnunlike behaviour, as does

Convents and the Body Politic in Late Renaissance Venice by Jutta

Gisela Sperling. The convent is also the one in which the heroine is

confined in Michelle Lovric’s novel

The Remedy.

Ruskin wrote

Early Renaissance, and fine of its kind; a Gothic chapel attached

to it is of great beauty. It contains the best John Bellini in Venice,

after that of San G. Grisostomo, "The Virgin, with Four Saints;" and is

said to contain another John Bellini and a Tintoret, neither of which I

have seen.

Henry James wrote

... the Madonna of San Zaccaria, hung in a cold, dim, dreary

place, ever so much too high, but so mild and serene, and so grandly

disposed and accompanied, that the proper attitude for even the most

critical amateur, as he looks at it, strikes one as the bended knee.

Bibliography

In centro et oculis urbis nostre : la chiesa e il monastero

di San Zaccaria

Marcianum Press 1996

Details the recent restoration work and is my source for the old plan

above and the photos of the back of the high altarpiece from the old

church and of the cloisters.

Opening times

Daily 10.00 – 12.00 & 4.00 - 6.00

Sacristy, chapels and crypt.

Where once you paid a nice man a €1.50 entry fee these spaces are now run

by Chorus and are open

11.30 - 5.00. But you can now get in with your Chorus pass, and it's the

same man.

Cloister access

It is reportedly possible to see the two cloisters (see below) of the convent if you

ask the Carabinieri nicely. There has also been art for sale in the rooms

in the ex-convent behind the small fenced garden to the right of the

church's entrance.

But not recently. Rooms created out of the area just behind the

entrance to the old church are currently shamefully just used for storage.

Vaporetto San Zaccaria

map

|

|

|